Questions about humanity make 'Blade Runner' and 'The Thing' a killer double-feature

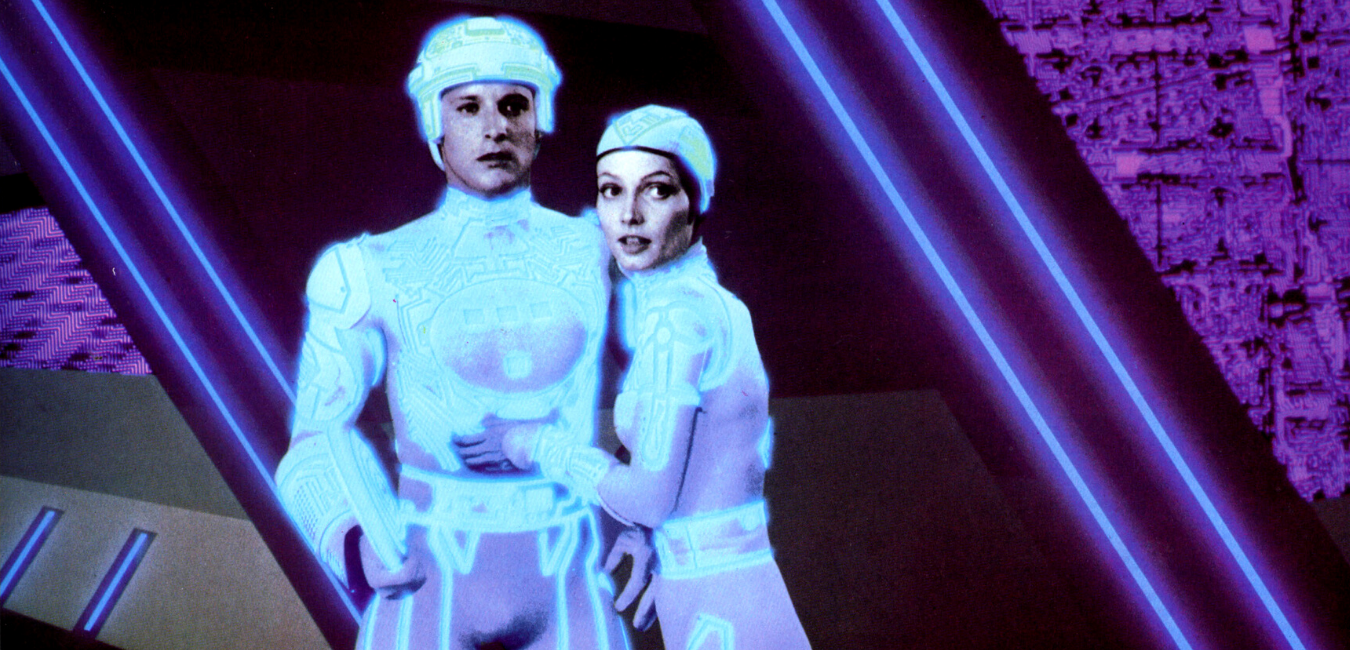

Harrison Ford (left) and Kurt Russell are not sure if they’re hunter or hunted in “Blade Runner” and “The Thing.” (MovieStillsDB.com)

"Blade Runner"

Directed by Ridley Scott

Released June 25, 1982

Where to Watch

"The Thing"

Directed by John Carpenter

Released June 25, 1982

Where to Watch

Once the characters of "The Thing" first encounter a shape-shifting alien that's taken the form of one of the crew members, Garry, the station's shell-shocked commander, can't believe what he's just seen.

"I've known him for ten years. He's my friend," Garry says after burning alive the lifeform; he thought he was a friend.

The characters of John Carpenter's "The Thing" and Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" are both perplexed by people around them, doubting if they are who they say they are. And if they are not human, what does it make them? The two movies also share another feature: They both bombed in theaters during their initial release, crowded out of an intense marketplace, only for critics and fans to reassess with praise later on. Now "Blade Runner" and "The Thing" are considered two of the greatest genre classics of the 1980s. As we celebrate their 40th anniversary, what more can these masterworks teach us about humanity?

"The Thing" takes us to a United States research station in Antarctica, as a dog is being pursued by a rival Norwegian group into the station. It turns out the Norwegians unintentionally uncovered an alien frozen in the ice, one that can assume the forms of any man or creature and react violently if threatened. Soon the Americans, led by Kurt Russell's MacReady, find themselves trapped in a remote location, unsure if their coworkers are allies or enemies.

You really have to feel for these poor guys. First, they are trapped in a hostile, remote location with their coworkers: Some you know better than others, but forced together nonetheless because of the job. Now this Thing infiltrates the compound, causing you to doubt everything around you. The biologist Blair (Wilford Brimley) is one of the first to fully realize the implications of what the Thing can do and promptly loses his mind, causing the rest to completely isolate him in the compound. The next time we check in with Blair, he pleads with the rest to set him free, but nobody mentions the noose hanging beside Blair.

But the flip side of humanity is also on display in "The Thing." When faced with an unknown lifeform in their compound, the immediate reaction of these men is to kill it and ask questions later. They are also quick to turn on each other, the seeds of their innate distrust exploding from within, which will likely expedite the speed of their ultimate fate. Notably, there are no women stationed here in Antarctica, and nearly everybody with an expressed opinion has no other plan than to identify the Thing, isolate it, and kill it. Would there have been another outcome if these men tried to communicate with this admittedly grossly disturbing lifeform, like an episode of "Star Trek?" We can't say based on the film, but I would suspect the immediate hostility between the parties involved is not a plot weakness but a thematic point.

The film is a remake of 1952's "The Thing from Another World" by Howard Hawks. When Carpenter caught word producers wanted him to remake it, he was initially pessimistic about the project but found a way in after reading John Campbell's short story, "Who Goes There?"

"It was the creepiness of the imitation business, and the questions that it brought up that I thought were really interesting," Carpenter told Creative Screenwriting in 1999. "I also thought it was timely that in remaking the short story, I could be true to my day making this movie, just like Hawks was true to his day when he made his. And there was something else, that whole 'who goes there?' – it was a spooky idea."

There is also an element of not knowing who's for real in "Blade Runner," a neo-noir science fiction thriller that starred Harrison Ford. In the near future, the "Blade Runner" world will be filled with replicants: engineered biomechanical androids designed to do the work the rest of humanity doesn't want to do. Rick Deckard (Ford) works as a blade runner, someone who hunts replicants on the run.

"Replicants are like any other machine," Deckard says early on. "They're either a benefit or a hazard. If they're a benefit, it's not my problem."

He reconsiders his opinion when he meets Rachael (Sean Young), another replicant created by Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkle), who doesn't realize her origin until it is revealed to her. Rachael expresses thoughts and emotions to Deckard. She remembers her childhood via implanted memories, but from an outside perspective, does that make her significantly different from any other person who recalls something that didn't actually happen but feels real enough?

As Deckard unwinds the mystery behind these replicants, it makes him question what specifically makes replicants who they are and what makes him, him. Now graced with self-awareness, Rachael goes on the run from the Tyrell Corporation and questions if Deckard would hunt her. Deckard likes her too much to do that, but admits that wouldn't stop another blade runner from accepting the assignment.

Meanwhile, the leader of the rogue replicants, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), goes through with a plan to meet his maker: Tyrell. The replicants are created with an artificial lifespan of four years. As Batty and his compatriots reach the end of this timeline for themselves, he pushes Tyrell to solve this issue. It gives us insight into the motivations of these replicants but also poses philosophical questions about the nature of what makes us human. Do our desires, intelligence, memories, and will to live define us? Do we have power over creations that also have those attributes?

While "The Thing" concludes with a fatalistic note, Roy stands above a vulnerable Deckard near the end of "Blade Runner" and decides to let him live, then muses poetically about how memories are also lost in death. Two science fiction movies were released on the same day, one set in the present and the other in an isolating, oppressive future. Still, each managed to strike different themes about the concept of humanity.

Forty years later, "The Thing" and "Blade Runner" offer glimpses of the future and human nature that still speak to audiences today. While our present conditions haven't quite turned into the stylized urban industrial center that the 2019 timeline of "Blade Runner" offers, we do share the dehumanizing elements seen in that society that looks to enforce structures and punish individuals simply based on their class level. Politics and social media have further inflamed the divisions in society, causing many of us to incredulously look at our friends and family in negative ways. The conditions and themes of these movies have seemingly morphed together in a grotesque mirror of ourselves, a spiritual version of Rick Bottin's acclaimed makeup effects on "The Thing."

There is no doubt that our modern era is dispiriting, but when watching this particular double-feature, I'm thankful that, by chance, I watched "Blade Runner" last. It turns the final scenes into a moment of grace, filled with mercy and hope. It may only last a minute, like Roy's tears in the rain, but it does remind us of our shared humanity if we only hope to see it.

Upon opening, both movies suffered under the cultural juggernaut that was "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial." "Blade Runner" opened in second place but made less than half its first weekend than "E.T." did in its third. "The Thing" opened in eighth place, and it would never get better. The films quickly fell out of theaters, with "The Thing" topping at $19.6 million and "Blade Runner" at $27.6 million. However, as cable movie channels began to come into homes across the United States, "Blade Runner" and "The Thing" found the audiences they were looking for in living rooms. The opening of the home video market also helped rebuild the legacy of these two genre classics.

Critics, however, were not incredibly kind at the time.

"'The Thing' is a great barf-bag movie, all right, but is it any good," asked Roger Ebert in his original review for The Chicago Sun-Times. "I found it disappointing for two reasons: the superficial characterizations and the implausible behavior of the scientists on that icy outpost. This material has been done before and better, especially in the original 'The Thing' and in 'Alien,' there's no need to see this version unless you are interested in what the Thing might look like while starting from anonymous greasy organs extruding giant crab legs and transmuting itself into a dog."

"Blade Runner" also opened to mixed reviews. The movie's theatrical edit features Ford's narration that actively detracts from Scott's intentions. A decade after its release, Scott released a director's edit of "Blade Runner" that excises the narration and then produced another "Final Cut" version of the film in 2007 that remains the superior version.

"This flamboyant attempt by (Scott) to synthesize an ominous, futuristic setting with the motley cliches of hard-boiled detective fiction is at best a freakish success," wrote Gary Arnold for The Washington Post. "The movie might just as well be happening in a future of simultaneous urban decay and hi-tech advancement that evolved without the specific impetus of a global catastrophe. Unfortunately, the loss of this context leaves the filmmakers at a thematic loss. They try to compensate with a dense, brilliant scenic texture, but it still doesn't compensate for the lost, or at least misplaced, context."

Now you'll find much more praise for the films, sometimes even more than box-office champ "E.T." As a young lad in 1982, I wasn't at the age to see these movies in the theater. But now they sit in my library collection, aging like a fine wine, bringing up new impressions and emotions with every viewing.

At the Box Office: "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" continues its reign as the summer's top movie, pulling in another $13.2 million over the weekend. However, this is also an illustration of how movie-going habits have changed in 40 years.

Most blockbuster films nowadays earn the majority of their money in the first few weekends of release while quickly breaking records for a weekend, or sometimes, even a day. In its third weekend of release, "E.T." hasn't even made more than $60 million, as "Rocky III" and "Porky's" remain the two biggest hits of the year at that point. "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan," "Poltergeist," and "Conan the Barbarian" are also within range of "E.T.'" box office gross. "E.T.'s" strength lies in continuing to post eight-figure grosses every weekend for several months as it slowly but surely becomes the biggest film of all time.

Behind "Blade Runner's" $6.1 million was "Firefox" in third place, earning $5.1 million in its second weekend. The sequels "Rocky III" and "Star Trek II" round out fourth and fifth place with $5 million and $4.5 million in returns, respectively.

Beyond the top five, "Annie" and "Poltergeist" were higher earners than the other two debuts, "The Thing" in eighth place with $3.1 million, and the family science-fiction adventure film, "Megaforce," in ninth with $2.3 million. While "The Thing" obviously would find a second life, "Megaforce" lacked both the deeds and words to become anything but a cult film of its time.

Next Week: “The Secret of NIMH”

Mark is a longtime communications media and marketing professional, and pop culture obsessive.